"Fred Derry: How long since you been home?"

"Al Stephenson: Oh, a couple-a centuries. "

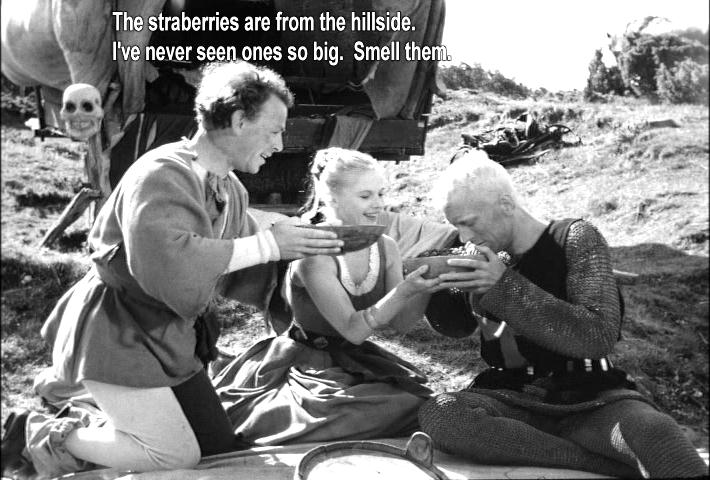

The movie about what happens to soldiers after their return home from the war is one that is still on the AFI top 100 films of all time. This movie, brilliantly cast, won all the major awards at the Academy Awards in 1947 including Best Actor for Fredric March. March’s performance as a banker turned Sergeant is just one of the reasons this movie will remind us in years to come that war is hell, and so is afterwards.

"The most fundamental value of mise-en-scene is that it defines our location in the material world: the physical settings and objects that surround us indicate our place in the world," (Corrigan White 85). Through the superb story structure and characterization, these potentially painful topics are handled with care. The three stories of the veterans, fold into each other. The men, who have never met before a fateful flight home, become lifelong friends.

+2.jpg) Multiple close up and aerial shots are used in the beginning to give the audience a feel as to what the soldiers are experiencing. Al (March), is shown in his uniform, proud, and also eager to see his family. Homer, played by Harold Russell, is scared and nervous to go home. He has lost both his hands in the war and now uses prosthesis. Fred, played by Dana Andrews, was a newlywed a month before he signed up for the war. He has no idea what to expect when he returns. He only knows for sure is that he no longer wants to be a soda jerk. After returning home, then men continue to bond and stay current in each other’s lives.

Multiple close up and aerial shots are used in the beginning to give the audience a feel as to what the soldiers are experiencing. Al (March), is shown in his uniform, proud, and also eager to see his family. Homer, played by Harold Russell, is scared and nervous to go home. He has lost both his hands in the war and now uses prosthesis. Fred, played by Dana Andrews, was a newlywed a month before he signed up for the war. He has no idea what to expect when he returns. He only knows for sure is that he no longer wants to be a soda jerk. After returning home, then men continue to bond and stay current in each other’s lives.The story of Al is one that connects all three. Al is at first uneasy being home. We see a close up him embrace his family, but almost as if he is looking right through them not recognizing them. He returns to his job as a banker and receives a promotion. A big project for someone to take on that just returned to civilization. Al can’t control his inner demons and begins to turn to alcohol for solace. He turns to the bar which Homer’s Uncle owns and meets up with Fred. A night of drinking ensues and the patchwork of the three characters turns into one story. It leaves the audience wanting more, feeling as though these veterans could be someone you might know.

At one point, all three of the men go through an identity crisis; separately yet together. They haven’t quite figured out if they should continue to be soldiers or become the regular Joe next door. The strong supporting actors including Al’s wife and daughter, played by Myrna Loy and Teresa Wright respectively, play an important role in defining the three veterans and bringing them back to reality. In one scene in particular, we see Fred looking in the mirror while he is holding a photograph of himself his wife kept on the dresser. We all look to the mirror for answers. The truth though is staring right at us. We see what we want to believe is real. Fred sees for the first time he has become someone he no longer wants to be. He wants to be the family man he was before the war. As for the other characters, Homer stops his self pity and becomes the man he wants to be, a great husband to his wife. Fred also becomes the man he wants to be. He divorces his wife and finds that true happiness might be a struggle but the rests, just like war, in the end are worth it.

At one point, all three of the men go through an identity crisis; separately yet together. They haven’t quite figured out if they should continue to be soldiers or become the regular Joe next door. The strong supporting actors including Al’s wife and daughter, played by Myrna Loy and Teresa Wright respectively, play an important role in defining the three veterans and bringing them back to reality. In one scene in particular, we see Fred looking in the mirror while he is holding a photograph of himself his wife kept on the dresser. We all look to the mirror for answers. The truth though is staring right at us. We see what we want to believe is real. Fred sees for the first time he has become someone he no longer wants to be. He wants to be the family man he was before the war. As for the other characters, Homer stops his self pity and becomes the man he wants to be, a great husband to his wife. Fred also becomes the man he wants to be. He divorces his wife and finds that true happiness might be a struggle but the rests, just like war, in the end are worth it. The Best Years of our Lives. Director William Wyler. Starring Frederic March, Dana Andrews, Harold Russell, Myrna Loy, Teresa Wright. MGM. DVD. 2000.

Corrigan & White (2009), The Film Experience: An Introduction.